Blue Sky Ideas

Perspectives from The Artist's Road

The desert Southwest holds many charms for the landscape painter, not the least of which are the amazing skies. The higher the elevation, the more intense those sky colors become. We have spent many happy hours over the years painting in and around Santa Fe, New Mexico, which is at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo mountains and sits at an elevation of around 7,500 feet. The very dry climate combined with altitude makes the blues in an ordinary sky extremely intense in chroma, value and temperature—the big three color spaces.

We thought it would be interesting to apply those concepts to a real life landscape photo of northern New Mexico as a color exercise, but with a practical twist. Many painters employ photos as reference in their studio work, and even use Photoshop to correct the often skewed colors that cameras and phones in particular render. But trying to paint from a computer image has its problems and limitations. A big issue is that the computer screen uses an RGB system of light transmission to render an image. The more color saturation one adds to an image actually makes it brighter, and is referred to as an Additive System. Pure White is the result of adding all the RGB colors together, full strength. Paint is a reflective, or Subtractive System, so the addition of more color to a mix results in a darker color and mixing them all together eventually results in Black. A color’s temperature relates to whether it leans toward cool or warm. Its value is how close it is to black or white. Its chroma is the perceived strength of the color as it reflects from a surface compared to white, and is an important characteristic of pigment. A color with high chroma has no black, white, or gray added to it. So one can have any combination of those three characteristics in any color mixture.

What happens when we try to match those incredible colors of the desert sky in paint? One thing soon becomes very clear—one can match the hue and value, but it is nearly impossible to achieve the same chroma as light in the sky or even on a screen. There is no substitute for painting that sky from life, of course, but we are still limited by the chroma contained in the tube color. This demonstration attempts to illustrate how light can be translated into paint.

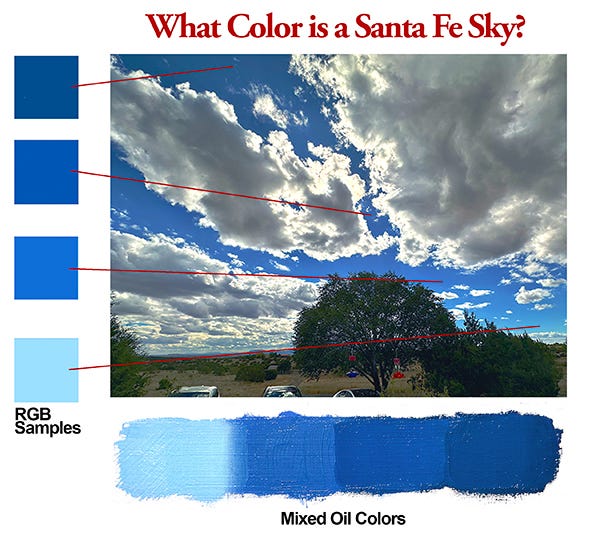

The vertical column of colors represent swatches that were sampled in Photoshop from the photograph we took in New Mexico, and which we color-corrected first. Our screen was set to show us colors in RGB, balanced by the system software. It is interesting to note that small swatches of color surrounded by white often look quite different from the larger mass of color in which they sit. (See: Interaction of Color: Revised and Expanded Edition, by Josef Albers.)

The painted color string below the photograph is my attempt to mix those samples and match all three characteristics with the subtractive system of paint. One might think that painting a blue sky from dark to light would simply require either lightening or darkening a color or color mix. This will not result in a believable sky in my experience. As the sky seems to near the horizon, we are looking through more dust, smoke and pollution, so the sky takes on a warmer and sometimes yellower tint. At altitude, ground colors can even reflect back up into the clouds and sky.

I used a mix of Cobalt and Ultramarine for the darkest blues at the top, the next swatch was slightly greener, so I mixed mostly Cobalt with a touch of Prussian Blue and White, the next, Cobalt and White and finally Sevres Blue and White near the ground. Not bad, but not what I saw. The painter must then, play a little trick on the viewer to make them believe in our sky by carefully adjusting ALL OTHER COLORS in our painting to make the sky look brighter and more chromatic. It is a lesson all landscape painters learn sooner or later, and is a skill which serves us well as picture-makers.